To understand how delusion arises, practice watching your mind. Begin by simply letting it relax. Without thinking of the past or the future, without feeling hope or fear about this thing or that, let it rest comfortably, open and natural. In this space of the mind, there is no problem, no suffering. Then something catches your attention – an image, a sound, a smell. Your mind splits into inner and outer, self and other, subject and object. In simply perceiving the object, there is still no problem. But when you zero in on it, you notice that it’s big or small, white or black, square or circular; and then you make a judgment – for example, whether it’s pretty or ugly. Having made that judgment, you react to it: you decide you like it or don’t like it. That’s when the problem starts, because “I like it” leads to “I want it.” We want to possess what we perceive to be desirable. Similarly, “I don’t like it” leads to “I don’t want it.” If we like something, want it, and can’t have it, we suffer. If we don’t want it, but can’t keep it away, again we suffer. Our suffering seems to occur because of the object of our desire or aversion, but that’s not really so – it happens because the mind splits into object-subject duality and becomes involved in wanting or not wanting something.

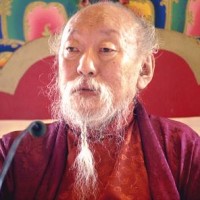

Chagdud Tulku Rinpoche

from the book

Read a random quote or see all quotes by Chagdud Tulku Rinpoche.

Further quotes from the book Gates to Buddhist Practice :

- Reducing self-importance

- No overnight change

- Acceptance of what we have

- Stopping the extreme swings of the emotional pendulum

- Changing the way the mind experiences reality